Throwing Italians out of Little Italy

By Harvey D. Shapiro

“It became necessary to destroy the village in order to save it.”

That ironic quotation, attributed to an American military officer during the Vietnam War, captures the plight of Adele Sarno, the daughter of Italian immigrants, who is being forced out of the apartment she has occupied for 50 years in New York’s Little Italy. She is being evicted by none other than the Italian American museum, an institution dedicated to memorializing the Italian immigrant experience in New York.

That ironic quotation, attributed to an American military officer during the Vietnam War, captures the plight of Adele Sarno, the daughter of Italian immigrants, who is being forced out of the apartment she has occupied for 50 years in New York’s Little Italy. She is being evicted by none other than the Italian American museum, an institution dedicated to memorializing the Italian immigrant experience in New York.

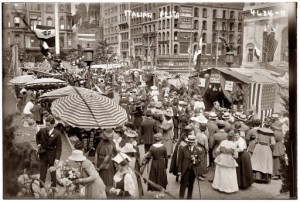

Sarno, who has lived in the same apartment since 1962, ran a Little Italy store selling candy and other Italian products for many years. When she was 16 years old, she was the Queen of Little Italy’s celebrated Feast of San Gennaro, which honors the patron saint of her father’s hometown, Naples. She still attends the church where she was baptized, Little Italy’s Church of the Most Precious Blood, founded by Italian immigrants in the late. And her apartment is said to be filled with marble tables and ceramics from the old country. The irony in her story is as thick as a good marinara sauce. The Italian American Museum “purports to exhibit Italian-American culture and then proceeds to evict a living artifact.” That’s how this melodrama was described by Victor J. Papa, director of the Two Bridges Neighborhood Council, an affordable housing group that had been assisting Sarno in her efforts to stay in her apartment. Papa told the press that the Museum’s approach is “absolute hypocrisy.” Many say that an organization dedicated to preserving Italian-American culture should not be evicting one of a dwindling number of those who embody that culture. The trouble is Sarno has been paying only $820 a month rent for her two bedroom apartment, while others in the same building were paying more than five times that amount. By all accounts, she was a model tenant, but the Italian American museum has been trying to evict her for financial reasons.  After a series of court battles, in April her lawyers ran out of legal maneuvers and a judge ruled that she would have to move out of her apartment by the end of June. It’s likely that she will go to live with her only child, a daughter who lives in Wisconsin, a Midwestern state a thousand miles from Little Italy. Populated largely by descendants of Scandinavians and Germans, Wisconsin is not an easy place to get good pasta. The battle over Sarno’s apartment reflects the changes that have taken place in Little Italy, the iconic neighborhood where many of New York’s earliest Italian immigrants settled more than a century ago. But that was then. More recently, the 2010 U.S. Census did not record a single Little Italy resident who was born in Italy. And a 2013 census found that only 554 of the neighborhood’s 7816 residents indicated they had any Italian ancestry. The changes are visible all around: To be sure, second and third generation Italians still flock to the restaurants on weekends, as do tourists from around the world. But the proprietors of the shops selling “Kiss me I’m Italian” buttons are often Asians. So are the people going up the stairs to the apartments over those shops. Third generation Italians may be the proprietors of the area’s many Italian restaurants and gelato emporiums, but their kitchen staffs are largely Mexican and Asian. And the Italian “social clubs,” once the hangout of prominent Mafioso, have all but disappeared..

After a series of court battles, in April her lawyers ran out of legal maneuvers and a judge ruled that she would have to move out of her apartment by the end of June. It’s likely that she will go to live with her only child, a daughter who lives in Wisconsin, a Midwestern state a thousand miles from Little Italy. Populated largely by descendants of Scandinavians and Germans, Wisconsin is not an easy place to get good pasta. The battle over Sarno’s apartment reflects the changes that have taken place in Little Italy, the iconic neighborhood where many of New York’s earliest Italian immigrants settled more than a century ago. But that was then. More recently, the 2010 U.S. Census did not record a single Little Italy resident who was born in Italy. And a 2013 census found that only 554 of the neighborhood’s 7816 residents indicated they had any Italian ancestry. The changes are visible all around: To be sure, second and third generation Italians still flock to the restaurants on weekends, as do tourists from around the world. But the proprietors of the shops selling “Kiss me I’m Italian” buttons are often Asians. So are the people going up the stairs to the apartments over those shops. Third generation Italians may be the proprietors of the area’s many Italian restaurants and gelato emporiums, but their kitchen staffs are largely Mexican and Asian. And the Italian “social clubs,” once the hangout of prominent Mafioso, have all but disappeared..

2

Little Italy was one of several ethnic enclaves in lower Manhattan: Nearby was the Lower East Side where massive numbers of Eastern European Jews arrived between 1880 and 1920, and north of that was Little Odessa, where thousands of Ukrainians settled. South of Little Italy there was Chinatown. But as the offspring of these ethnic groups have prospered, they have generally chosen to move to nicer neighborhoods, opening up spaces for other groups to move in and diluting the original ethnicity of these neighborhoods. The exception is Chinatown where the population is growing rapidly as a result of a continuing massive influx of Chinese immigrants. Indeed, in the last few years the Chinese population has swarmed across historic ethnic lines, and Chinese language signs are all over Little Italy as well as the Lower East Side. Gentrification has also been pricing out many of the original residents of the ethnic neighborhoods. On what was once the northern end of Little Italy, for example, the chic shops and pricey residential lofts in Soho are encroaching on traditional Italian territory.

Little Italy was one of several ethnic enclaves in lower Manhattan: Nearby was the Lower East Side where massive numbers of Eastern European Jews arrived between 1880 and 1920, and north of that was Little Odessa, where thousands of Ukrainians settled. South of Little Italy there was Chinatown. But as the offspring of these ethnic groups have prospered, they have generally chosen to move to nicer neighborhoods, opening up spaces for other groups to move in and diluting the original ethnicity of these neighborhoods. The exception is Chinatown where the population is growing rapidly as a result of a continuing massive influx of Chinese immigrants. Indeed, in the last few years the Chinese population has swarmed across historic ethnic lines, and Chinese language signs are all over Little Italy as well as the Lower East Side. Gentrification has also been pricing out many of the original residents of the ethnic neighborhoods. On what was once the northern end of Little Italy, for example, the chic shops and pricey residential lofts in Soho are encroaching on traditional Italian territory.

As their populations have shifted, each of the ethnic enclaves has sought to memorialize its history with a museum. There is now a Ukrainian Center, a Chinatown Museum, and a tenement museum on the Lower East Side. An Italian American Museum was created in 2001; it’s mission statement says it is “dedicated to the struggles of Italian-Americans and their achievements and contributions to American culture and society.” The museum was originally in mid-Manhattan, but in 2008 it bought three adjacent buildings in Little Italy for $9 million. The plan was to turn the building, which included six apartments, into a museum, but the financial crisis and recession that began in 2008 resulted in a funding shortfall. Now the museum is said to be hoping to sell its three buildings to a real estate developer, with part of the sale to include rent-free space for the museum in whatever structure is erected. Meanwhile, the museum would like to maximize its income from the rental apartments. For months, efforts to raise Sarno’s rent have been thwarted by legal proceedings claiming she is protected by various laws limiting rent increases. Although the courts have now ruled against Sarno, it may prove to be a pyrrhic victory of the museum. Throwing out an 85 year old Italy grandmother who has lived in the same apartment since 1962 is not exactly a good way to generate contributions from the offspring of Italian immigrants. It’s difficult not to feel sympathetic when Sarno tells a reporter, “I’m not going to be here that many more years. Let me die in my home.” But the Italian American Museum has not been moved. Little Italy “is not a community of Italian-Americans any longer,” according to Joseph V. Scelsa, the foundation and director of the museum. He and his colleagues at the museum argue that the Italian legacy will endure only if there is a viable Italian Americn Museum. The Sarno case has meant confronting some painful “realities” in Little Italy, according to Joseph Sciorra, Director for Academic and Cultural Programs at the John D. Calandra Italian American Institute, Queens College, a part of the City University of New York. Sciorra told The New York Times, “The sort of everyday lived experience of the place as a residence of Italian Americans for all intents has been over for decades.” Nonetheless, Little Italy has retained a place in the hearts and minds of Italian-Americans in the New York area. That, after all, is why there is an effort to build a museum there as opposed to elsewhere in New York City. But Sciorra also said that for a museum dedicated to Italian history in New York, throwing out Sarno shows “a lack of vision.” He is one of many who suggested she be kept on as a speaker or docent at the museum. She is, after all, “literally

3

the living embodiment of the living history of Little Italy,” as Sciorra put it. Unfortunately, it looks like those seeking her insights into the Italian immigrants’ experience in New York will soon need to head out to Wisconsin to talk to her.

Social